The Other Silent Killer

What is Osteoporosis and who is at risk? Osteoporosis is a disease of the skeletal system characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of the bone tissue.

While the symptoms of the disease seldom become debilitating until the latter stages of life, its propagation may begin much earlier.

While the symptoms of the disease seldom become debilitating until the latter stages of life, its propagation may begin much earlier.

Epidemic Proportions

According to statistics from the National Osteoporosis Foundation, 52 million Americans have low bone density or osteoporosis. 50% of women and 25% of men will break a bone after age 50 due to osteoporosis.  By 2020, half of Americans over 50 are expected to have low bone density or osteoporosis. A woman’s risk of breaking a hip is equal to her risk of developing breast, uterine and ovarian cancer combined.

By 2020, half of Americans over 50 are expected to have low bone density or osteoporosis. A woman’s risk of breaking a hip is equal to her risk of developing breast, uterine and ovarian cancer combined.

Proactive Prevention of Osteoporosis

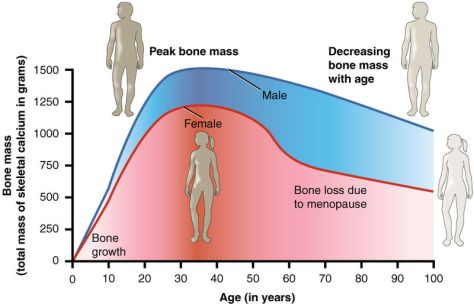

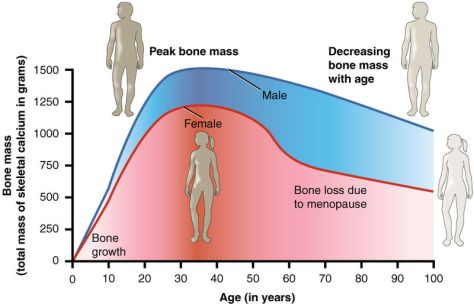

Bone density peaks around age 30 and subsequently declines. Adolescents and young adults should regularly participate in weight bearing activities in order to build up a “bone density reserve.”

The American College of Sports Medicine, ACSM, recommends physical activities that generate relatively high-intensity loading forces to augment bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents. Evidence suggests exercise-induced gains in bone mass in children are maintained into adulthood, suggesting that physical activity habits during childhood may have long-lasting benefits on bone health.

Treatment is Paramount

While Osteoporosis is preventable, it is not curable. The only option is treatment. Treatment of established osteoporosis is cost-effective irrespective of age (Kanis, et al, 2005). Studies have shown that bone mineral density in postmenopausal women can be maintained or increased with therapeutic exercise.

Basic Bone Anatomy

Bones are made from collagen, calcium-phosphate complexes, and bone cells. Bone tissue is living, and is constantly being remodeled. The underlying cause of osteoporosis is an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation. Excessive bone resorption, inadequate formation of new bone during remodeling, and inadequate peak bone mass are all mechanisms by which osteoporosis develops. Aging results in bone being lost more rapidly than it is formed.

Weight-bearing and Loading Exercise for Bone Health

Weight bearing activities like walking, jogging, dancing, stair climbing and hiking allow the force of gravity to act through the skeleton. Through this application of force, mechanisms that stimulate bone density are activated in response to the mechanical loading. The training principle of progressive overload is fundamental to the effective treatment of osteoporosis.

Exercise stimulates effective bone modeling/remodeling.

Exercise stimulates effective bone modeling/remodeling.

Strength Training for Bone Health

Impact loading exercises are superior to traditional weight-bearing activities for maintaining bone health. Impact loading exercise simply means any exercise that requires you to support your own body weight, including walking, aerobics or weightlifting.

Resistance training can be defined as the act of repeated voluntary muscle contractions against a resistance greater than what is normally experienced in daily life. Training of this kind is known to increase strength through changes in both the muscular and nervous systems. In one study, resistance training had more of an effect on bone strength in the hip and lower spine than walking alone (Harvard Men’s Health Watch, 2013). Nine months to a year of regular exercise should be afforded before appreciable increases in bone mass are detected. Proper form and technique are important. Volume, frequency, duration and other training variables should be specific to the condition of the individual. For individuals with diagnosed osteoporosis, the ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (Pescatello, et al, 2014) suggests the following guidelines for physical activity and resistance training aimed to prevent falls:

- One to three sets with five to eight repetitions of four to six weight-bearing, lower-body strength exercises using body weight as resistance

- Activities performed two to three days/week

- Additional resistance may be applied gradually and conservatively

(up to 10 lbs.) with weighted vest

- Therapy bands & rubber tubing may be used to facilitate

range-of-motion exercises

- Avoid impact exercise, spinal flexion against resistance, spinal

extension, high compressive forces on the spine, quick trunk rotation

Aerobic Training

Aerobic training is also important to the overall efficiency of the system, and in maintaining bone mass. Aerobic exercises are a system of physical conditioning, such as running, walking, swimming, or calisthenics strenuously performed so as to cause a significant temporary increase in respiration and heart rate. Activities that engage larger muscles like walking, cycling, swimming, and water walking are recommended for overall health, however claims that aerobic exercise can build bone density are false. According to ACSM, “Although aerobic exercises are beneficial and important for overall fitness, they don’t specifically help build bone density”.

Non-Impact Exercises

While non-impact exercises may not directly support bone mass, they still offer immense indirect benefits in the treatment of osteoporosis. Balance exercises (e.g. Tai Chi, aquatic exercises) heighten proprioception and reduce the risk of falling, which is the leading cause of lost independence among the elderly.

Postural exercises improve posture and help support the spine. Functional exercises improve the ability to perform activities of daily living, increasing quality of life and maintaining independence. Individuals who practice Tai Chi have 47% less falls and only 25% of the hip fractures of those who do not (Province, et al, 1995). Tai Chi can be beneficial for stunting bone loss in weight-bearing bones in early postmenopausal women (Chan, et al, 2004).

Dietary Approaches to Fighting Osteoporosis

Calcium and Vitamin D – Two of the most important nutrients in fighting osteoporosis are calcium and vitamin D. Calcium is an important component of the bone matrix, while vitamin D assists in its absorption. Supplementation with vitamin D has improved lower extremity muscle performance and reduced risk of falling in several high-quality double blind randomized control trials (Bischoff-Ferrari, et al, 2009). The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine of the

National Academies, National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements recommends the following intake levels for post-menopausal women:

- Calcium: 1200 milligrams/day

- Vitamin D: 10 micrograms/day (400 International Units/day) from ages 51 to 70 (Increase to 15 micrograms/day [600 International Units/day] after age 70)

Protein – Aging may compromise the body’s ability to process protein efficiency. Older adults should be vigilant in their consumption of protein in order to avoid protein malnutrition. In one study with elderly men and women, higher dietary protein intake was associated with a lower rate of age-related bone loss (Hannan, et. al, 2000).

______________________________

References

American College of Sports Medicine

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, et al. (2009) Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J 339:b3692.

Center for Disease Control. – Calicium

Chan, K; Qin, L; Lau, M; Woo, J; Au, S; Choy, W; Lee, K; Lee, S. A randomized, prospective study of the effects of Tai Chi Chun exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:717–22.

Daltroy, L. H., Larson MG, Eaton HM, et al. Discrepancies between self-reported and observed physical function in the elderly: the influence of response shift and other factors. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1549–61. Medline:10400256.

Hannan MT, Tucker KL, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. (2000) Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 15:2504.

Hartard M, Haber P, Ilieva D, et al. (1996) Systematic strength training as a model of therapeutic intervention. A controlled trial in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 75:21.

Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, et al. (2005) Intervention thresholds for osteoporosis in the UK. Bone 36:22

Kemmler W, Lauber D, Weineck J, et al. (2004) Benefits of 2 years of intense exercise on bone density, physical fitness, and blood lipids in early postmenopausal osteopenic women: results of the Erlangen Fitness Osteoporosis Prevention Study (EFOPS). Arch Intern Med 164:1084.

Kerr, D., Ackland, T., Maslen, B., Morton, A. and Prince, R. (2001), Resistance Training over 2 Years Increases Bone Mass in Calcium-Replete Postmenopausal Women. J Bone Miner Res, 16: 175–181. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.1.175

National Osteoporosis Foundation.

Palombaro, K. M., Black, J. D., Buchbinder, R., & Jette, D. U. (2013). Effectiveness of Exercise for Managing Osteoporosis in Women Postmenopause. Physical Therapy, 93(8), 1021-1025. doi:10.2522/ptj.20110476

Pescatello L, Arena R, Riebe D, Thompson PD, ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, American College of Sports Medicine, 9th ed., 2014, Philadelphia : Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health

Preisinger E, Alacamlioglu Y, Pils K, et al. (1995) Therapeutic exercise in the prevention of bone loss. A controlled trial with women after menopause. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 74:120.

Province MA, Hadley EC, Hornbrook MC, et al. (1995) The effects of exercise on falls in elderly patients. A preplanned meta-analysis of the FICSIT Trials. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. JAMA 273:1341.

Raisz, L. (2005). “Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects”. J Clin Invest 115(12): 3318–25

Strength Training is Better for Bones. (2013). Harvard Men’s Health Watch, 2013 Jul;17(12):8.

_______________________________

This article is written by Kevin McMahan, a Health and Wellness Educator for the Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance. Kevin has had a lifelong interest in health and wellness. After graduating from Carmel High School he went on to get an associates degree in social sciences from Monterey Peninsula College, and a bachelors in kinesiology from California State University Monterey Bay. He is a certified personal trainer through the American College of Sports Medicine. “Your health is your wealth”, is something that he always likes to say. The Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance is a registered 501 (c) 3 nonprofit health and wellness education organization. For more information about the Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance contact us or visit our website at www.montereybayholistic.com.

This article is written by Kevin McMahan, a Health and Wellness Educator for the Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance. Kevin has had a lifelong interest in health and wellness. After graduating from Carmel High School he went on to get an associates degree in social sciences from Monterey Peninsula College, and a bachelors in kinesiology from California State University Monterey Bay. He is a certified personal trainer through the American College of Sports Medicine. “Your health is your wealth”, is something that he always likes to say. The Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance is a registered 501 (c) 3 nonprofit health and wellness education organization. For more information about the Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance contact us or visit our website at www.montereybayholistic.com.

Disclaimer: The Monterey Bay Holistic Alliance is a charitable, independent registered nonprofit 501(c)3 organization and does not endorse any particular products or practices. We exist as an educational organization dedicated to providing free access to health education resources, products and services. Claims and statements herein are for informational purposes only and have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The statements about organizations, practitioners, methods of treatment, and products listed on this website are not meant to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. This information is intended for educational purposes only. The MBHA strongly recommends that you seek out your trusted medical doctor or practitioner for diagnosis and treatment of any existing health condition.

0.000000

0.000000

By 2020, half of Americans over 50 are expected to have low bone density or osteoporosis. A woman’s risk of breaking a hip is equal to her risk of developing breast, uterine and ovarian cancer combined.

By 2020, half of Americans over 50 are expected to have low bone density or osteoporosis. A woman’s risk of breaking a hip is equal to her risk of developing breast, uterine and ovarian cancer combined.

Researchers recruited 89 stroke survivors – most of whom had ischemic strokes. The study was a randomized prospective study conducted outside of a hospital setting. The average age of participants was 70 years old. Forty-six (46) percent were women. Most of the participants were college educated, Caucasian, and living in or around Tucson, Arizona. The majority of the participants had had a stroke within three years prior to the research study.

Researchers recruited 89 stroke survivors – most of whom had ischemic strokes. The study was a randomized prospective study conducted outside of a hospital setting. The average age of participants was 70 years old. Forty-six (46) percent were women. Most of the participants were college educated, Caucasian, and living in or around Tucson, Arizona. The majority of the participants had had a stroke within three years prior to the research study.

A recent study entitled, “Stress in America™: Missing the Health Care Connection,” was conducted online by Harris Interactive on behalf of the

A recent study entitled, “Stress in America™: Missing the Health Care Connection,” was conducted online by Harris Interactive on behalf of the